By Evan Gough

It’s easy to forget that the Hubble has been in space since 1990. That’s going on 30 years now. And during that time, it’s been serviced and had its cameras upgraded.

Image Credit: J. Trauger, JPL and NASA/ESA via Wikimedia Commons

The camera responsible for these “staircase” images is the Wide Field and Planetary Camera 2 (WFPC2). It was installed on the Hubble Space Telescope in 1993 during Servicing Mission 1 by the Space Shuttle Endeavour. WFPC2 was operational until 2009, when it was replaced by the Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC3).

WFPC2 is senses light in different wavelengths, infrared, ultraviolet, and visible. It has four identical CCDs, each one 800 x 800 pixels. Three of them are arranged in an “L” pattern, and make up the Wide Field Camera. The fourth one has a narrower focus for capturing more detailed images of a smaller part of the WFPC’s view.

Typically, the view of all four CCDs is combined, and it’s the fourth CCD with a narrower focus that fills in the small square in the “L” shape. That’s because its higher magnification means the image form the fourth CCD needs to be shrunk in order to align with the other three.

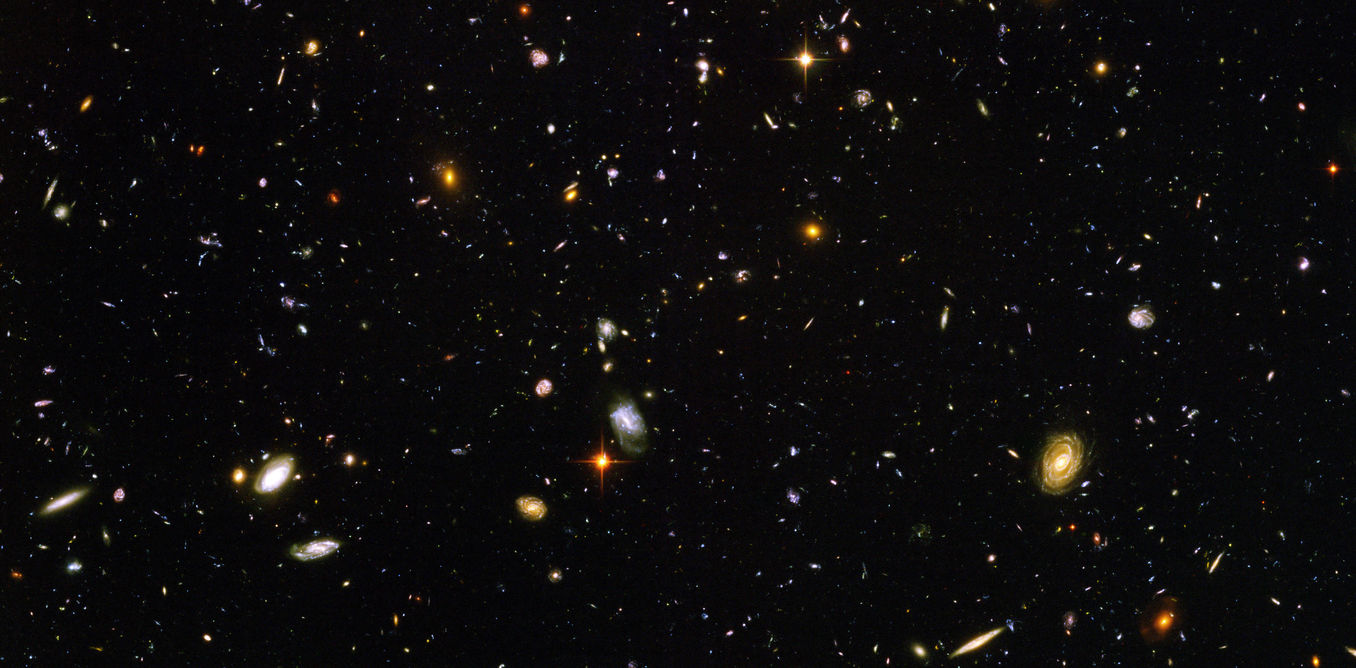

This image of the Hubble Deep Field shows how the four separate sensors combine to create the telltale staircase image that WFPC2 is known for. - Image Credit: Image Credit: John Fader via Wikimedia commons - Transfered to Commons by Mike Peel

It’s worth pointing out that most of these staircase images are just for us, interested members of the public. Scientists using the Hubble to study objects in space have access to the full-resolution images of the Planetary Camera portion of the image.

Spiral Galaxy M100 (NGC 4321) as imaged by the WFPC2 on the Hubble. - Image Credit: J. Trauger, JPL and NASA/ESA via Wikimedia Commons

In 2009, the WFPC2 was replaced by the Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC3) during Hubble Servicing Mission 4 (STS-125, Space Shuttle Atlantis.) WFC3 also sees in optical, UV, and infrared, but doesn’t have a CCD with a separate magnification. So it doesn’t have that “annoying” staircase missing piece.

Since there are no more servicing missions scheduled for the Hubble, and there are no more space shuttles to perform them, WFC3 was designed to see the Hubble through to the end of its mission, whenever that sad day will be.

This image of the Pillars of Creation in the Eagle Nebula was captured by the newer WFC3. No staircase! It was taken as a tribute to the original Hubble WFPC2 image, but this one is much higher resolution thanks to the updated technology. - Image Credit: NASA, ESA, and the Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA) via Wikimedia Commons

NASA thinks that the Hubble could keep going through the 2020s, but at some point it will stop working. The original plan for the venerable Space Telescope was to retrieve it with a shuttle. But, obviously, that’s not going to happen. (Who knows, maybe one of these billionaire space entrepreneurs will go up and get it. Imagine the cachet!)

A uncontrolled re-entry would probably not destroy the Space Telescope completely, and there’s risk of human fatalities depending on where it comes down. But NASA was thinking ahead. As part of the final servicing mission in 2009, NASA installed the Soft Capture Mechanism (SCM) and the Relative Navigation System (RNS). Together, they’re called the Soft Capture and Rendezvous System (SCRS). That system gives NASA some options to safely de-orbit the Hubble.

Until, then Hubble is still a busy, working science instrument, and one that gives us a steady diet of science eye-candy. Enjoy.

Source: Universe Today

If you enjoy our selection of content please consider following Universal-Sci on social media: