When we talk about “Earth-like” worlds, it is tempting to picture blue oceans and white clouds and stop there. But the bigger mystery is what happens much earlier, when a newborn solar system is still just a swirling disk of gas, dust, and tiny rocks. In that chaotic stage, small differences can steer a planet toward becoming a mostly rocky world like Earth or something very different. A new study suggests one of those differences may be surprisingly common, and it may begin with a dramatic event happening nearby, long before any planet looks like a planet at all.

Researchers led by Ryo Sawada and colleagues examined an old question with a fresh angle: how often do young solar systems get the right mix of short-lived radioactive elements that can shape the kinds of rocky planets they end up making? Their results point to a scenario that could make Earth-like outcomes more likely than some earlier models suggested.

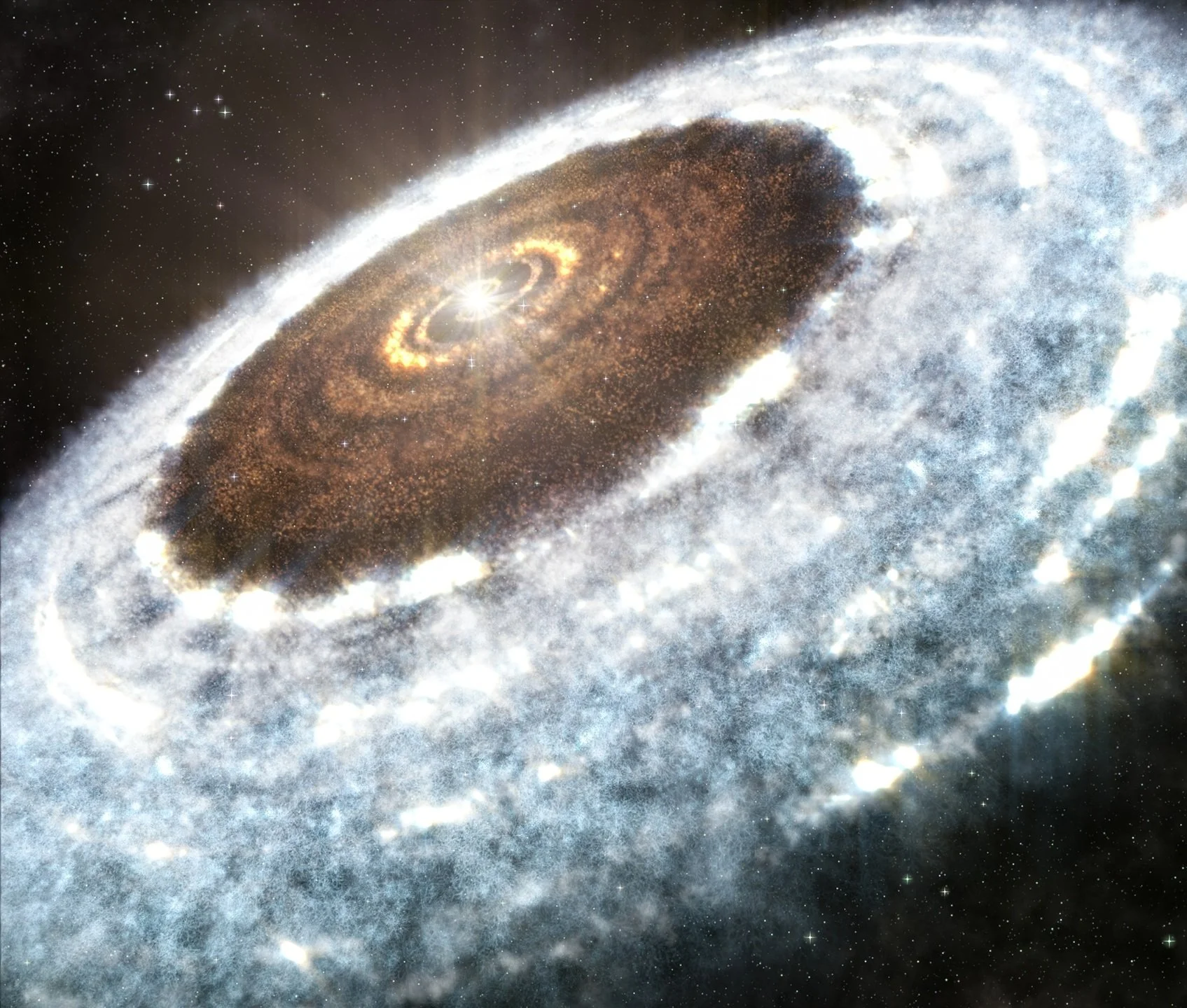

Image Credit: Andamati via Shutterstock / HDR tune by Universal-Sci

A strange “fingerprint” in meteorites hints at an early heater

Some of the best clues about the early Solar System do not come from telescopes, but from meteorites. When scientists analyze certain meteorites, they find evidence that short-lived radionuclides, meaning radioactive forms of elements that decay over a few million years or less, were present across the early Solar System.

One of the most important is aluminum-26. As it decays, it releases heat. According to the authors, that heat could have warmed early planet-building bodies enough to drive off water and other easily lost materials. In other words, it may have helped turn initially wetter building blocks into drier, more rock-dominated ones, a pathway many researchers connect to forming planets with low overall water content more like Earth than like an “ocean planet.”

The catch is that these radionuclides should not have lasted long enough to simply be left over from the giant molecular cloud that formed the Sun. So where did they come from, and how did they end up distributed through the disk without ruining the disk itself?

The supernova problem: enough material, but not too much damage

For years, a nearby supernova has been a leading candidate. A supernova can produce and eject radioactive material, and if a young solar system is close enough, some of that material could be incorporated into the planet-forming disk.

But “close enough” is where earlier explanations run into trouble. Models that try to deliver enough aluminum-26 and other short-lived radionuclides by direct supernova injection often require the explosion to be extremely close. That raises a serious issue: too close, and the shock and radiation can disrupt or strip away the very disk needed to build planets.

The new study aims to solve that tension, not by removing the supernova from the story, but by changing what the young disk gets from it.

A cosmic-ray bath that changes what a young disk can make

Sawada and colleagues propose what they call an “immersion” mechanism. The idea is that when a nearby supernova goes off, its expanding shockwave does not only carry debris. It also contains huge numbers of energetic particles, cosmic rays, that can be trapped in the shocked region.

In their scenario, a young star’s planet-forming disk experiences the passing supernova environment at a distance of around 1 parsec, about 3.26 light-years. At that distance, the disk is more likely to survive. But it can still be exposed to a heavy dose of energetic particles associated with the shock.

Those particles can trigger nuclear reactions inside the disk itself, producing some short-lived radionuclides “in place” rather than requiring all of them to be delivered as supernova material. The team’s model combines two contributions: some isotopes come from direct injection of supernova debris, while others are created within the disk due to irradiation by these trapped cosmic rays.

According to the study, this combined approach can reproduce the general pattern of multiple short-lived radionuclides inferred from meteorites to within about an order of magnitude, which the authors argue is within the uncertainties involved. The key point is that this can happen at a distance that avoids the disk-destruction problem that challenges many injection-only models.

Why this could make Earth-like planets less rare

A theory is only as interesting as its real-world chances. The authors also looked at whether a supernova at roughly this distance is a realistic event for young solar systems.

Their argument centers on star clusters. Many Sun-like stars form in clusters, and clusters often include massive stars that live fast and explode as supernovae while nearby younger stars still have planet-forming disks. According to the authors’ estimates, solar-mass stars in typical cluster environments may often experience at least one supernova within about 1 parsec during the lifetime of their disks. They also suggest this is more likely than the much closer distances some earlier models require.

If that is right, then Solar System-like amounts of aluminum-26 and other short-lived radionuclides may not be unusual. And if those radionuclides help dry out early planet-building material, then the conditions that favor water-poor, rocky planets could be more common than previously thought.

It is important to be clear about what this does and does not mean. It does not mean most planets are Earth twins, or that life is common. It does suggest that one part of the chain, the early radioactive heating that can influence whether rocky planets end up water-rich or relatively water-poor, may occur in a meaningful fraction of Sun-like systems.

That matters because it changes how we think about the starting line. If more planetary systems begin with Earth-like ingredients, then finding rocky planets with more Earth-like water budgets may become more plausible as exoplanet surveys expand.

This research connects a very early event, a nearby supernova and its energetic particle environment, to a much later outcome: the types of rocky planets that form. It also makes a practical prediction in spirit, if not a simple one-to-one forecast: if young solar systems in clusters often undergo this kind of “immersion,” then surveys that target habitable zones around nearby Sun-like stars may find that Earth-sized rocky planets are not as exceptional as once believed.

The universe still has plenty of ways to make planets unlike Earth. But this study suggests it may also have more ways to make Earth-like ones than we used to assume.

Sources and further reading on the subject of Space & Exploration:

Cosmic-ray bath in a past supernova gives birth to Earth- like planets - (Science Advances)

If the Universe Is Expanding, What Is It Expanding Into? - (Universal-Sci)

How Large Is The Universe? - (Universal-Sci)

How do astronomers know the age of the planets and stars? - (Universal-Sci)

Too busy to follow science news during the week? - Consider subscribing to our (free) newsletter - (Universal-Sci Weekly) - and get the 5 most interesting science articles of the week in your inbox

FEATURED ARTICLES: