Predicting seizures has proven to be a difficult feat in the past. There have been attempts to develop early warning systems to help anticipate such occurrences; however, even the best efforts yield a warning time of only a few minutes before a seizure occurs. According to researchers, brain implants may solve this problem, allowing for predictions several days ahead.

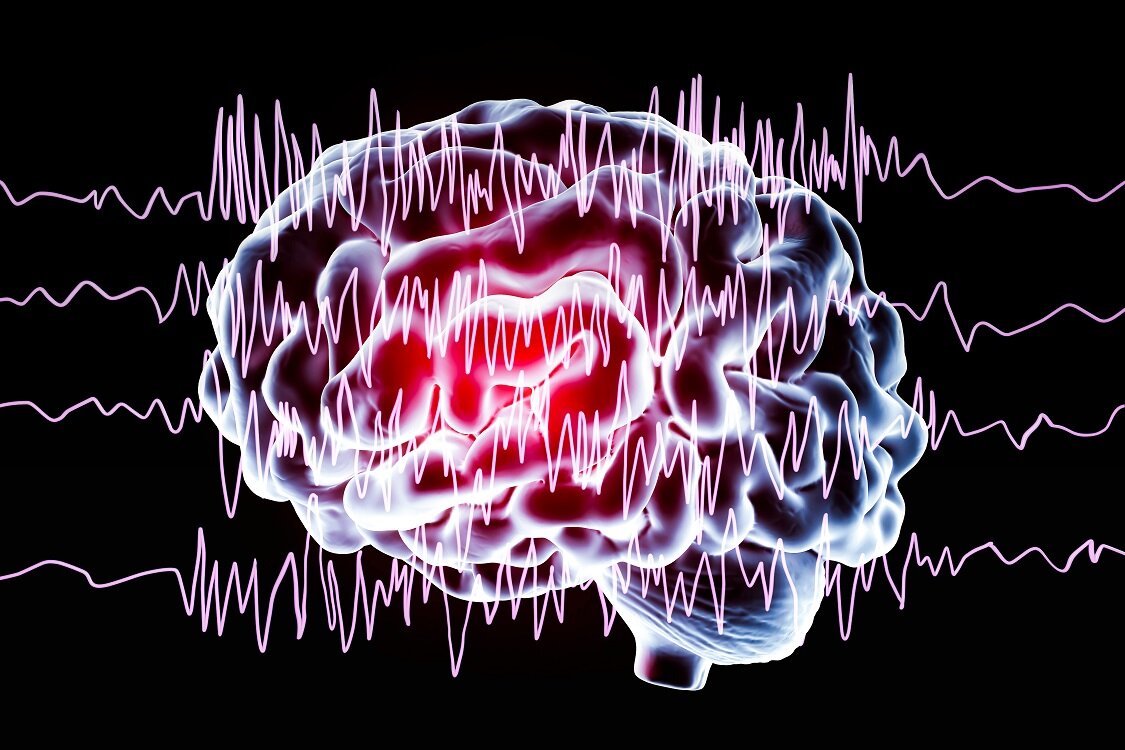

Image Credit: Rainer Fuhrmann via Shutterstock / HDR tune by Universal-Sci

A seizure is the result of abnormally excessive or synchronous neuronal activity in the brain. They ordinarily last for only a few minutes or even less. Symptoms range from a slight temporary loss of awareness to trembling involving just a part of the body with varying levels of consciousness, to uncontrolled shaking movements involving much of the body with loss of consciousness.

Approximately 5% of all adults will deal with a seizure at least once in their life. Seizures can, in some cases, become life-threatening when the patient develops breathing problems. One can understand that scientific progress in predicting these attacks is, therefore, of great value.

For many years, scientists from around the globe have been working to distinguish patterns of electrical activity in the brain that indicate an impending seizure, sadly with poor results. Technology has proven to be a limiting factor here.

Recently a group of neuroscientists analyzed data generated by contemporary brain implants and determined that it is finally possible to reliably anticipate seizure risk in epilepsy patients several days in advance.

The scientists used data from the UCSF Epilepsy Center in San Fransisco (USA). This center has been acting on the front line of brain implant stimulation device utilization. Such a device can stop seizures by accurately stimulating the brain at the first indications of an impending seizure. Over time these devices have built a treasure trove of data from patients.

By analyzing this data, the researchers learned that seizures are less random than they seem on the surface. They recognized weekly-to-monthly cycles of "brain irritability" that predict a higher probability of having a seizure. Consequently, they set out to test whether these regular patterns could be applied to produce clinically reliable predictions of seizure risk.

Image Credit: Kateryna Kon via Shutterstock / HDR tune by Universal-Sci

The team developed forecasting algorithms, which were then tested against data from 157 study participants. Looking back at the trial data, the researchers were able to identify periods of time when patients were nearly ten times more likely to have a seizure than at baseline, and in about 40% of patients, signs of these periods of heightened risk could even be detected several days in advance.

According to Vikram Rao, neurologist, and co-senior author of the study, it has been the first time that anyone has been able to predict seizures a number of days ahead in time in a reliable manner.

Naturally, the model cannot predict exactly when a seizure will happen. A heightened risk of a seizure doesn't even mean a seizure will ultimately happen. Precise knowledge of how exactly a seizure is triggered is still lacking. Currently, however, some people that suffer from epilepsy cannot partake in possible dangerous activities like, for example, bathing or engaging in sports as the perceived threat of a seizure is persistent. These new findings might enable people to start planning their lives around when they're at high or low risk.

Although further research is still needed as the accuracy of the predictions still varies from patient to patient, the current findings are a giant leap in the right direction and might better the lives of millions of people worldwide in the not too distant future.

If you’re interested in a more extensive description of the study, be sure to check out the paper published in The Lancet Neurology listed below

Sources and further reading:

FEATURED ARTICLES:

If you enjoy our selection of content please consider following Universal-Sci on social media