The late physicist Stephen Hawking made a huge contribution to cosmology during his lifetime, but he didn’t quite manage to resolve all the mysteries of the universe. Now one of the last papers he ever worked on has been published – and it introduces some new ideas about the size and shape of the cosmos. But what does the research actually say and how important are the findings?

How many of earth’s moons crashed back into the planet?

For decades, scientists have pondered how Earth acquired its only satellite, the Moon. Whereas some have argued that it formed from material lost by Earth due to centrifugal force, or was captured by Earth’s gravity, the most widely accepted theory is that the Moon formed roughly 4.5 billion years ago when a Mars-sized object (named Theia) collided with a proto-Earth (aka. the Giant Impact Hypothesis).

The carbon footprint of tourism revealed (it’s bigger than we thought)

Breathing lunar dust could give astronauts bronchitis and even lung cancer

It’s been over forty years since the Apollo Program wrapped up and the last crewed mission to the Moon took place. But in the coming years and decades, multiple space agencies plan to conduct crewed missions to the lunar surface. These includes NASA’s desire to return to the Moon, the ESA’s proposal to create an international Moon village, and the Chinese and Russian plans to send their first astronauts to the Moon.

Other planets stretch out Earth’s orbit every 405,000 years

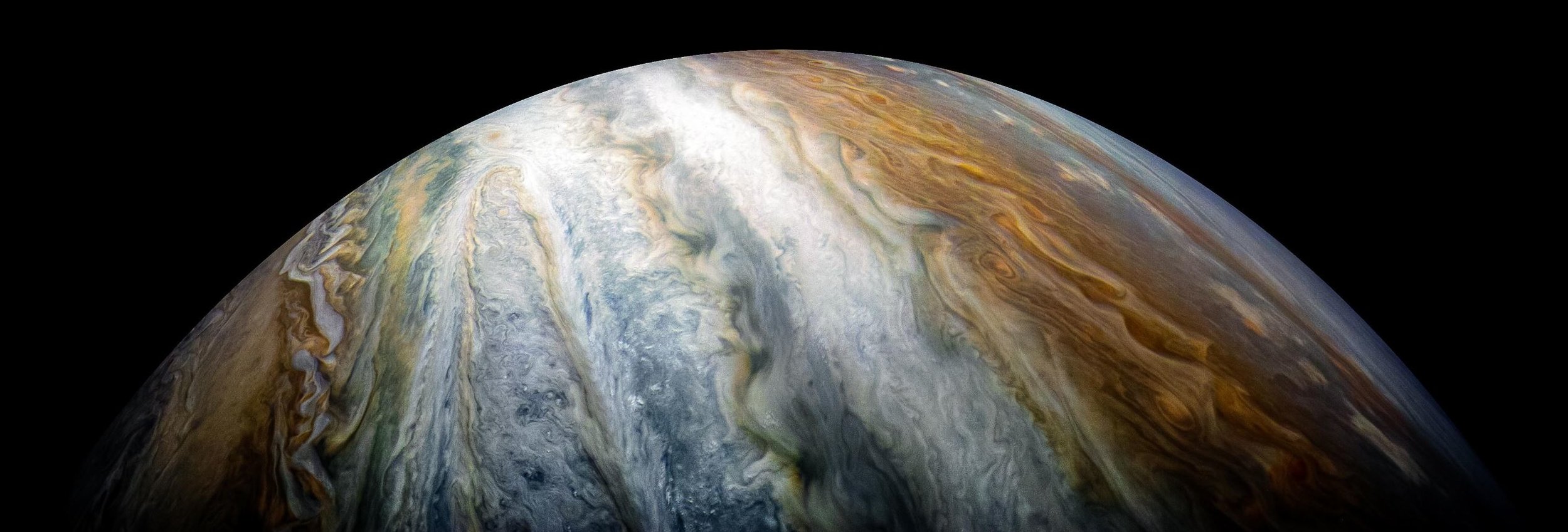

The latest from Juno as Jupiter appears bright in the night sky

NASA Satellite Images Show Fissures from Hawaii Volcano

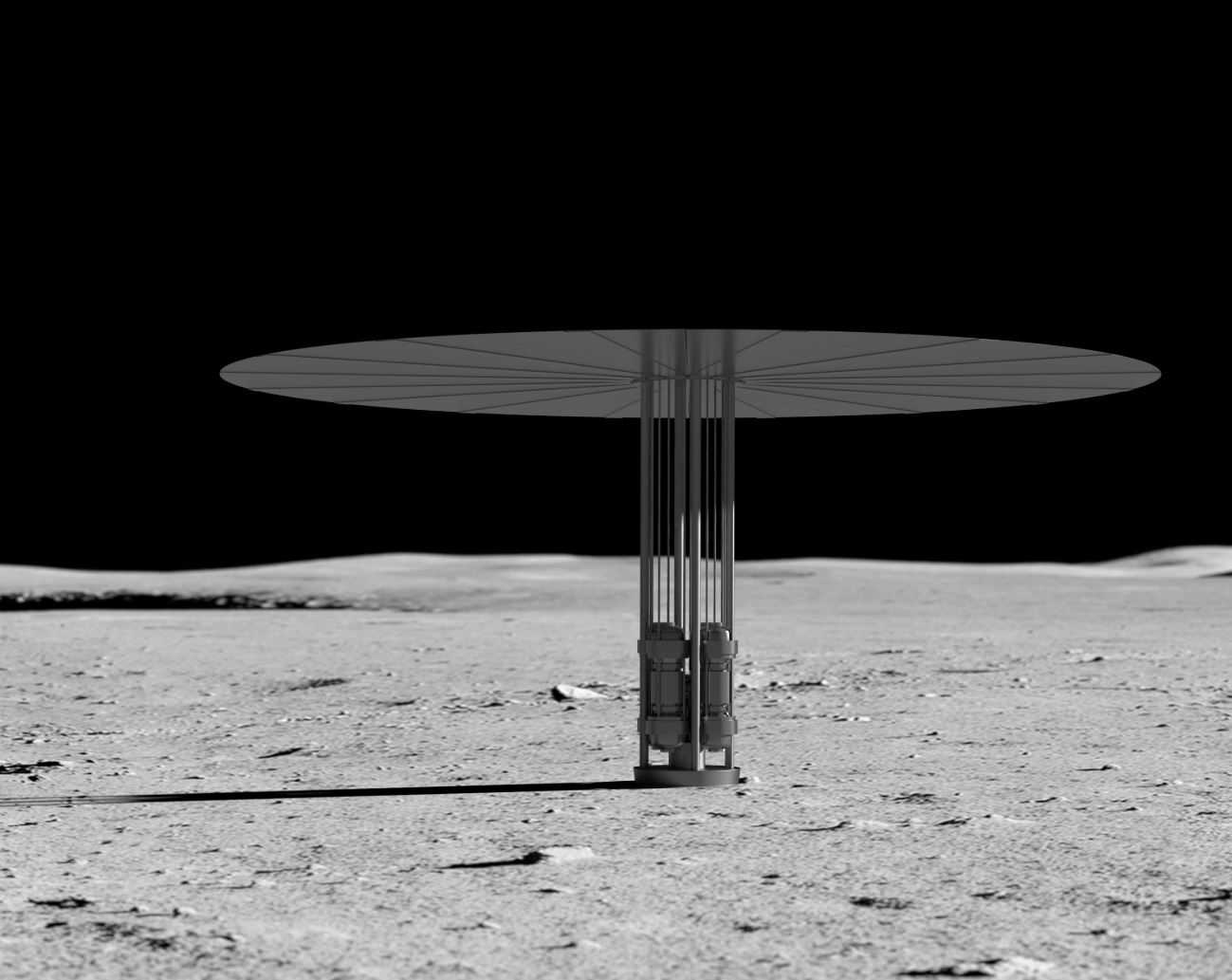

We Now Have A Working Nuclear Reactor for Other Planets — But No Plan For Its Waste

One of the TRAPPIST-1 planets has an iron core!

In February of 2017, a team of European astronomers announced the discovery of a seven-planet system orbiting the nearby star TRAPPIST-1. Aside from the fact that all seven planets were rocky, there was the added bonus of three of them orbiting within TRAPPIST-1’s habitable zone. Since that time, multiple studies have been conducted to determine whether or not any of these planets could be habitable.

Mining asteroids could unlock untold wealth – here’s how to get started!

A virus ‘cocktail’ could one day treat food poisoning

Water-based battery stores green energy for later

Five amazing ways redesigning biological cells could help us fight cancer

Want to eat better? You might be able to train yourself to change your tastes

Elements from the stars: The unexpected discovery that upended astrophysics 66 years ago

Ancient Galaxy Megamergers - ALMA and APEX discover massive conglomerations of forming galaxies in early Universe

Scientists discover how to harness the power of quantum spookiness by entangling clouds of atoms

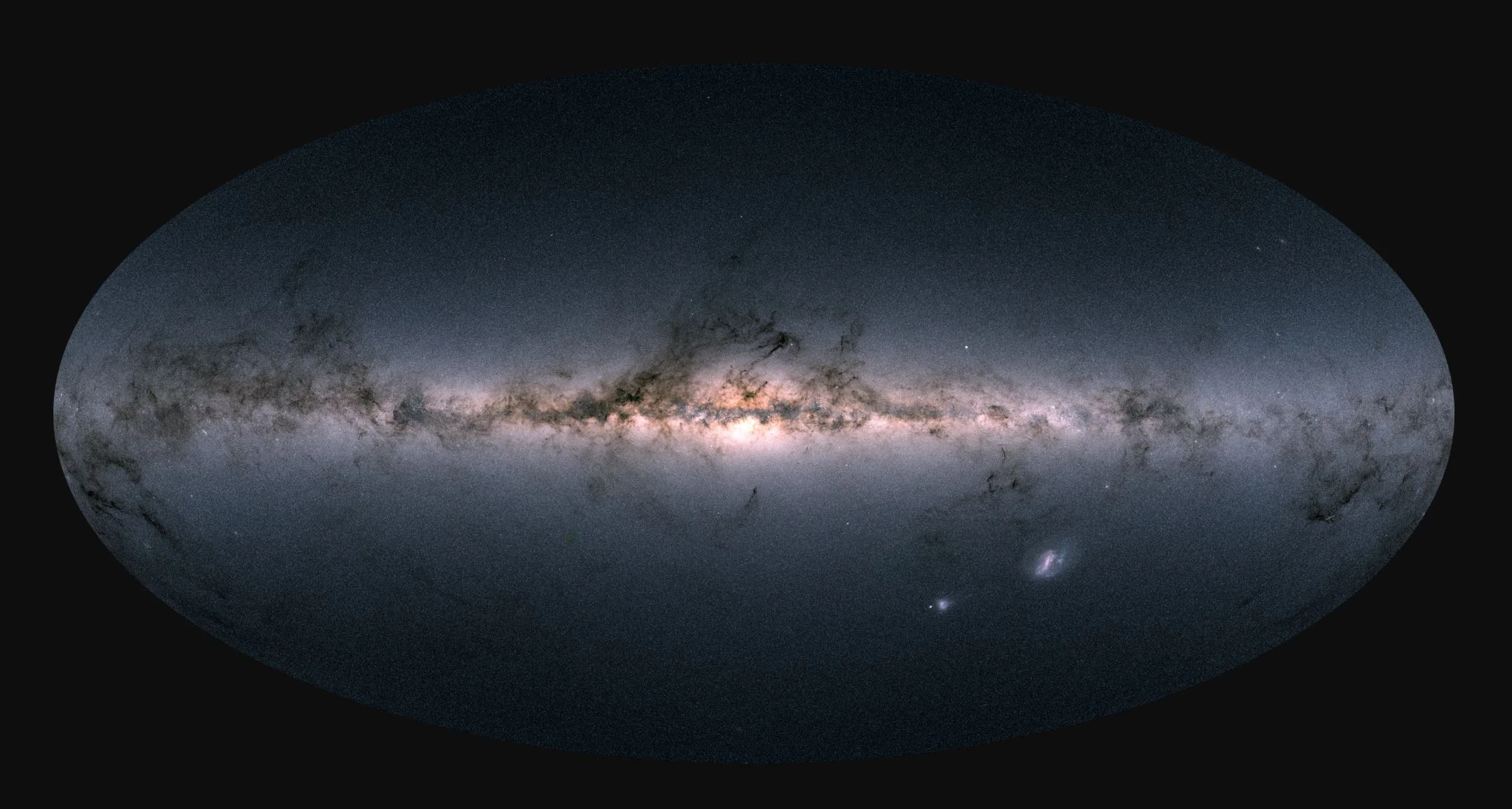

Gaia mission releases map of more than a billion stars – here’s what it can teach us

Most of us have looked up at the night sky and wondered how far away the stars are or in what direction they are moving. The truth is, scientists don’t know the exact positions or velocities of the vast majority of the stars in the Milky Way. But now a new tranche of data from the European Space Agency’s Gaia satellite, aiming to map stars in our galaxy in unprecedented detail, has come in to shed light on the issue.

How many planets is TESS going to find?

The Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), NASA’s latest exoplanet-hunting space telescope, was launched into space on Wednesday, April 18th, 2018. As the name suggests, this telescope will use the Transit Method to detect terrestrial-mass planets (i.e. rocky) orbiting distant stars. Alongside other next-generation telescopes like the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), TESS will effectively pick up where telescopes like Hubble and Kepler left off.

End of ageing and cancer? Scientists unveil structure of the ‘immortality’ enzyme telomerase

Making a drug is like trying to pick a lock at the molecular level. There are two ways in which you can proceed. You can try thousands of different keys at random, hopefully finding one that fits. The pharmaceutical industry does this all the time – sometimes screening hundreds of thousands of compounds to see if they interact with a certain enzyme or protein. But unfortunately it’s not always efficient – there are more drug molecule shapes than seconds have passed since the beginning of the universe.